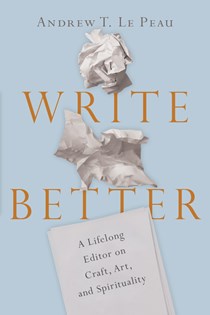

Tips & Tricks for the Aspiring Academic Author

By Andy Le Peau

Taken from Appendix H of Write Better

In many ways, academic publishing is its own world, especially when it comes to writing for scholarly journals. Often colleges and universities provide mentors for new faculty seeking to advance professionally, guiding them in the ways of publishing. Nonetheless, I often found professors making simple mistakes when it came to book publishing. Here are a few tips for smoothing the way to a contract.

I’m done with my dissertation, and now I’m thinking about my next project. Should I wait until my new book manuscript is finished before I contact an editor?

No. Academic editors often prefer to talk with you at a very early stage. Then they can offer suggestions on the shape a manuscript should take before you start. It is hard to tell an author, “You know, if you had just written your three-hundred-page manuscript this way instead of that way, we would be interested in it.” They feel reluctant asking you to go through all that work on speculation. As a result, instead of giving advice for completely revising the book, editors may simply say no. They don’t want to put someone through all that effort when the book still might not be published, even after it is reworked.

What’s better—to present one fully developed book idea or several partially developed ideas?

It’s better to briefly describe three or four ideas and then let the editor suggest which one or two have the most promise for the publishing house. That saves you time and the editor time. Then you can develop a fuller proposal on those that are requested.

Do I need an agent?

Agents are not required to work with most academic publishers. It is fine to approach the publisher on your own. If you use an agent, remember that the editor will still want to have direct contact with you about the content of the proposal.

How do I find an editor?

Talk to your academic colleagues who have published before. Do they have a name of an editor or publisher they would recommend? You can also go to academic conferences and stop by the book sales area to ask for an appointment with an editor from a publisher with a booth there.

Aren’t simultaneous submissions taboo?

That is usually the case for journal publishing, but for book publishing it is not typically a problem. Most academic publishers I know are fine with simultaneous submissions if you make it clear in your cover letter that you are presenting the proposal to several others at the same time.

I’m early in my academic career. I should probably wait to publish a book until I’m established, right?

It would seem to make sense to wait until the end of your career to publish, when you can finally consolidate all you’ve learned and taught successfully for decades. But that is often too late. It is hard, from a publisher’s perspective, for authors to start publishing just at the point when they are about to retire, leaving their discipline and all their connections. Publishers are looking for authors who are becoming known through presenting papers and publishing journal articles, who are active participants in the key discussions going on in their discipline, and who are networking with colleagues across the country and beyond. Publishers want to build authors whose reputations they can help develop over the course of several books.

I am new as an academic and have very little track record. How can I get a publisher to take me seriously?

One dimension to getting a book proposal taken seriously orbits around a word that is anathema to many academics—promotion. This conjures up pictures of hucksterism and selling patent medicines. But certain academically appropriate ways to do promotion can help publishers give you a second look.

A mentor or established scholar may be willing, for example, to give an up-front commitment to endorse your work. Mention that in the proposal. If he or she will actually write the endorsement so that it can be included in the proposal, so much the better. In fact, getting three or four colleagues to commit ahead of time would help a lot. Otherwise, in your proposal simply name those scholars you know personally who you would be willing to ask for endorsements. The better known these potential endorsers are, the better for your proposal.

Other kinds of promotion are equivalent to what you would do anyway to build your résumé—give papers at conferences, get articles published in academic journals or high-end journalistic venues such as the Washington Post, the New Republic, and the Wall Street Journal.

Another good option is writing for established scholarly blogs in your field that editors often frequent. You can also begin an academic blog on your own or jointly with some friends. It’s best to post at least weekly to keep it active. The advantage of blogging with others is that you don’t have to produce something every week. The disadvantage is that a group blog may not be quite as effective in establishing your own name in the academic conversation.

Remember, any editors worth their salt want to find bright, new talent with whom they can develop fruitful, long-term relationships. So, yes, you are at a disadvantage when you are relatively unknown and unpublished. But at the same time, you may be exactly what a publisher is looking for.

What else can I do to get a publisher to notice my work?

One possibility is to coauthor a project (whether book or article) with an established professor. Senior scholars will already have connections to editors and publishers who will automatically take their proposals seriously. One’s Doktorvater would be a likely candidate for such an effort. But others you have worked under or met in other contexts are possible.

While suggesting such an arrangement may seem to be an imposition on someone (from your point of view), remember that many academics take their role seriously as mentors to the next generation of scholars. They want to help others (especially their own students) get established. And if the topic of the project comports nicely with or extends the work of the mentor, he or she will be more likely to join you. Nonetheless, as the junior partner you should probably expect to do most of the work in such a joint project.

What can help me have a successful author-editor relationship?

Ask yourself, what do you want in a student? Probably you are looking for curiosity, teachability, flexibility, as well as a willingness to work hard and take direction. That’s what an editor is looking for in an author.

Those students who are too sure of themselves, too confident, are the ones you may have the hardest time with. They forget the years of experience and learning you have amassed and simply don’t show enough humility. Likewise, remember that while you may have published one or two or even six books, an editor will have published dozens or hundreds of books. Take advantage of that hard-earned wisdom.

Yet an editor is also looking for a partner. Students who are too passive aren’t what you want either. Editors want authors to bring something substantive to the table. Ultimately an author-editor relationship should also be a collaboration of equals.

What are academic publishers looking for?

Academic publishers usually do books in four categories: core texts, supple-mental texts, monographs, and reference books. If your proposal doesn’t easily fit in one of these slots, you’ll probably have a hard time getting it published.

Where do ideas for academic books come from?

Often good ideas for academic books arise when you just can’t seem to find the right book for a class that covers what you want your students to know or in the way you want to cover it. You can turn that frustration in a constructive direction by writing it yourself.

What about academics writing for a general readership?

Scholars often have excellent material for a general audience of thoughtful readers. But commonly, academics underestimate how much they will need to change their writing style to reach that audience. Often I will get a proposal from a professor who says the book will be for laypersons. But it is clear from the writing sample and the proposed table of contents that it is instead appropriate for graduate students—several levels above the supposed target audience.

Authors often assume knowledge of high-level vocabulary and background that general readers won’t have. Professors are often so immersed in their subject matter that they can’t remember what ordinary folks do not know.

General readers don’t want lots of footnotes, don’t want to know about your methodology, and certainly don’t want a literature review. They expect you to write in first-person, active voice, not third-person passive. They don’t want to wait until the last chapter to hear something practical. That should be found in every chapter. General readers will need stories and illustrations throughout to keep them motivated to read on. They will need concrete examples to help explain the theory you present.

Often academics can speak effectively to lay audiences. If that is your situation, try to write the way you talk. If it is not something you’ve done much of, then you might try to find opportunities to speak to lay audiences so you can hone your skills in reaching them.

What about self-publishing?

Self-publishing won’t help an academic who is trying to build a vita of peer-reviewed publications. But if you can’t find a publisher for your classroom book, sometimes self-publishing can be a good option to make it available to your students. And if it catches on beyond more than your institution, it can be a way to get an established publisher to take notice and consider it for traditional publication.

But keep in mind that self-publishing takes a lot of work to do it well (design, proofreading, editing, production, printing, warehousing, shipping, billing, etc.). Even self-publishing services may require authors to do a lot of work to prepare the electronic file to their specifications. And then your job isn’t over if you want it to be used beyond your own classes. Marketing and promotion follow.

How do I get started?

Perhaps even before you have a formal proposal, research the publishers who will be displaying at regional or national academic conferences in your discipline that you plan to attend. Review their websites to see what kinds of books they are doing. Ask your colleagues for their impressions. Then, early in the conference, ask if you can make an appointment with an editor while you are there. When you meet, ask questions. What are the editors looking for? What are common mistakes new authors make? What would they like to see in a proposal? Be ready to talk about yourself, your background, and your interests.

If I get a contract, can I negotiate terms?

For purely academic books, royalty rates, flat fees, and advances (if any) are usually fixed for first-time and even for many established academic authors. To ask too much about changing these could be seen as presumption or ignorance of the business of academic publishing, which is built on very slim or subsidized margins. Exceptions can include projects where the publisher sees significant potential for sales to general as well as academic markets. If you are lucky enough to have more than one contract offer, that may allow you to ask publishers if they want to match or better the terms of the stronger contract.

If you are curious, you can ask about marketing plans and make suggestions, but don’t expect any commitments, verbal or contractual. This goes for setting the retail price of the book. Most academic publishers know the market and their business model better than you. Ask if you have concerns, but consider it friendly input rather than a negotiation. (Some academic publishers market almost exclusively to libraries and set retail prices at $100, $200, or more. If a lower retail price is important to you, you will simply need to find another publisher.)

Many contracts will offer ten free copies of the published book you will receive (again, except for library publishers). If you need more copies to put in front of key influencers who will help spread the news about the book, ask if you could provide a list of influencers for the publisher to send copies to.

If the contract has a clause giving the publisher right of first refusal on the next project (especially at the same terms as the current contract—which would then include another next book clause!), I strongly recommend asking this to be deleted. First, it is extremely easy for an author to get around this by offering a lame proposal the publisher is sure to reject. Second, publishers should want you to do another book with them because they earned it rather than because you must. Exceptions could be a contract for several books at once or for a series.

Content compiled from the following sources: