How the Liturgical Church Transformed My Faith

By Makayla Payne

I didn't expect to become Anglican.

I had just moved to Illinois for seminary and was looking for a church. I had never been to an Anglican church, but one week I stumbled into one that met on campus. As I walked in, I took a bulletin filled with pages (and I mean pages) of liturgy. The leaders wore long robes and crossed themselves. The congregation read pre-written prayers. Scripture was recited from the Old and New Testaments, the Psalms, and the Gospels. All throughout I was encouraged to participate. This church was at once foreign, welcoming, mysterious, and beautiful.

As I began to attend regularly, my appreciation only grew. The liturgy began to soak into my bones, it felt. I was not a spectator in worship but a participant. Together we were speaking to God and not merely being spoken to.

It turns out I'm not the only one who found myself accidentally Anglican. Many in my church and at IVP would also say they "stumbled into" a liturgical church. Often coming from fundamentalist backgrounds or wearied in their faith, people have found the Anglican church a safe space to rebuild their relationship with God. "I was burned out on informational and inspirational sermons and looking for a reason to keep going to church every week," says Ted Olsen, IVP associate publisher and editorial director. IVP graphic designer, Chandler McCosh, also shares, "Though I was personally struggling to connect with God, I sensed that in some strange way, like the paralyzed man who was lowered through the roof by his friends to Jesus in Luke 5:17-26, the liturgy and the faith of this congregation were placing me before the feet of Jesus."

Many from Low-Church backgrounds, myself among them, found the Anglican church strange at first. "To be honest, I had no frame of reference for what 'Anglican' meant—I wasn't sure if it was Catholic or Protestant, liberal or conservative, or perhaps had something to do with angels," McCosh remembers. In her memoir, Beth Moore wittily describes her first experience in an Anglican church. She narrates her confusion when the leaders lined up for the processional, "Seemed obvious to me they were about to have a ceremony. We must have inadvertently visited on a special Sunday" (270). It turned out to be just a normal Sunday.

Even amidst the peculiarities, or perhaps because of them, the service was surprisingly comforting. There's a historical, theological, and aesthetic depth in the Anglican tradition that many today have come to love.

Entering the Liturgy

As someone who values embodiment, beauty, and art, it perhaps was a no-brainer that I'd end up in a liturgical tradition. Anglicanism is the "via media," or "the middle way" between Roman Catholicism and Protestantism. I've never felt the need to choose between common polarities we see today. The tradition holds the tension of body and mind, God's mystery and knowability, Word and sacrament, mundane and supernatural. It's expansive in its scope of the gospel and holistic in its approach to God's world. God's creation and human culture are not hindrances to the Christian life; they're avenues through which we can experience God more concretely. Anglicanism is very "on the ground" in that sense. I don't have to stop being human to engage with God. On the contrary, the wonder of God becoming human has become all the more magnificent.

Embodied Worship

The average Sunday is a sensory experience. In the corner of the sanctuary, there are a number of candles people can light to symbolize their prayers going up to God. The priests and deacons wear stoles and display banners according to the color of the liturgical season. Candles are lit on the altar. Leaders are anointed with oil before the service begins. Some congregations use incense. Symbols abound before our eyes.

It's all very tangible. Take an Ash Wednesday service for example. Most people recognize when someone has been to one. The black, ashen cross painted across your forehead is not discreet. It's a tangible mark of death on our bodies. This mark that reminds us "we are dust and to dust we shall return" jolts us to feel the weight of death in a way reading about death cannot do. It's cognitive, but it also brings us to the level of embodied experience.

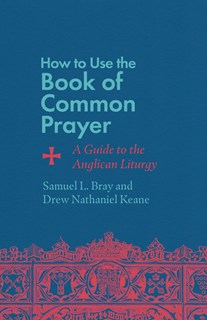

The Book of Common Prayer

The liturgy gives us words when we have none. There have been seasons when the only time I could pray was at church, and it was enough. Even full of anger, grief, and defiance, I've been comforted by a chorus of believers proclaiming the Nicene Creed, myself among them. Like Moses needing help to lift his arms, I need the prayers and help and hope of my sisters and brothers. That's exactly what the liturgy is: the thoughtful prayers of believers before us.

It's all encapsulated in one book: The Book of Common Prayer. The BCP provides the lectionary and liturgy for every imaginable service. It's also a guide for daily prayer. "The Anglican Morning Prayer service helps me every day," says Olsen. "Its prayers prompt me to pray for things I'd been forgetting to pray for in my extemporaneous praying. I'd expected liturgical prayer to become rote and mindless. Instead, they reorient me toward praise and confession and away from things in my life that create staleness and stagnancy."

The Book of Common Prayer teaches us to pray.

Word and Sacrament

In the service, Word and sacrament are equally important. The sermon is a bit shorter, since it shares the focal point of the service with the Eucharist. This small shift takes pressure off the leader to be the center of the service. When the service is about "us," it's no longer about me nor is it about the leader up front.

I entered the Anglican church while wrestling with whether I believed women could be pastors. My church's female pastor was a key reason I joined in the first place, though not all Anglican churches ordain women to the priesthood. I came to find the conversation around "what a woman can do" is completely different in High-Church contexts. No one bats an eye when a woman preaches; the concern is whether she can consecrate the bread and wine. I'm grateful my church empowers women to do both. I didn't know how badly I needed to see a woman preach on Sundays.

I also didn't know how much I longed for a joyful communion. In other churches I've attended, we've meditated on the death of Jesus in a way that highlighted the gravity of sin. This is important to do at times! But for my anxious conscience, the Eucharist as a time of "thanksgiving" soothes my soul. It reminds me how willing Jesus was to die for me, for us. "I love the joy of Eucharist—it is a feast!" says Theresa Hoffner, IVP's Divisional VP of Technology. "The tradition I came from was so scary and somber. I don't want to minimize the importance of respecting and taking Eucharist seriously, but I remember as a child being scared to touch the elements for fear that there might be an unconfessed sin that would make me unworthy."

The Eucharist is a feast and a mysterious one at that. I don't know exactly what happens when I take of Christ's broken body and blood, but I do know he meets me there. He is feeding and sustaining each of us with his very self in a mystical way. The Anglican emphasis on mystery reminds me the living God is still beyond my comprehension.

Walking Through the Church Calendar

The church calendar walks through the life of Jesus over the course of a year. The main seasons are Advent, which prepares us for Christmas, and Lent which prepares us for Easter. But there are lesser known seasons including Epiphany, Pentecost, and Ordinary Time. Interspersed throughout are the feast days of Jesus' disciples, Ascension Day, All Saints' Day, Trinity Sunday, and more.

This calendar determines nearly all the liturgy, which includes the Scriptures passages read, the prayers prayed, and the general order of the service. On any given Sunday, we're not only worshiping with our own congregation but with Anglican churches worldwide and throughout history.

Oriented Around Jesus

Structuring the year around the church calendar serves as a reminder that our whole lives are oriented around the life of Jesus. Participants often feel like they're at these events, being transported back to Jesus' time. This is especially the case with Holy Week—the week of Easter preceded by Palm Sunday, Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday. I remember driving to my church's 6 a.m. Easter service, in the stillness of the morning just before sunrise, and literally feeling like I was one of the women about to find Jesus risen at the tomb. It still brings tears to my eyes.

Others have said the same about the impact of Holy Week. "I came from a tradition where we only celebrated Easter Sunday, so I was deeply moved by journeying through Holy Week for the first time," McCosh shares. "It felt like rather than simply remembering the events, I was reliving the events—as if I were truly there." IVP associate editorial director Al Hsu also recalls, "In Holy Week and especially the Easter Vigil, we experienced the power of the resurrection in a way that felt like we were celebrating with millennia of fellow Christians."

Fasting and Feasting

Seasons of fasting and lament that precede the celebration, like Advent before Christmas, prepare us for the feast to come. Before we celebrate Jesus' birth, we survey why his coming was necessary in the first place. We enter the darkness. The church calendar makes room for all our emotions. At my church, this has led to an atmosphere of gentleness. By giving communal space for our complex suffering, I feel more attuned to the individual sufferings of those around me. When we honor our sorrow, joy becomes deeper. It's why Christmas is celebrated for twelve days and Easter for forty.

I tend to embrace the melancholic seasons more readily than the joyful ones. The church calendar stretches us to lean into the emotions we aren't comfortable with. The sorrow and the joy last longer than what we're typically used to. Yet this is its formative work.

Every season I experience more of the calendar's spiritual riches. Even after four years, I still don't have it all figured out. I hope I never do. And to those feeling drawn to a liturgical church, I hope you experience the wonder of participating yourself.

Discover more by reading the Fullness of Time Series and exploring the resources below.

About the Author

Makayla Payne is a recent Master of Divinity graduate from Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. She's passionate about writing theology beautifully and making it accessible to the church. She's particularly interested in the issues of gender and trauma. In her free time, Makayla enjoys exploring the Chicago food and coffee scene, painting, and quality time with friends. You can connect with her at makaylapayne.com.