Book of Common Prayer (International Edition) Free Resources & FAQ

The Book of Common Prayer (1662) is one of the most beloved liturgical texts in the Christian church, and remains a definitive expression of Anglican identity today. But the classic text of the 1662 prayer book presents several difficulties for contemporary users, especially those outside the Church of England.

The 1662 Book of Common Prayer: International Edition gently updates the text for contemporary use. State prayers of England have been replaced with prayers that can be used regardless of nation or polity. Obscure words and phrases have been modestly revised—but always with a view towards preserving the prayer book's own cadence. Finally, a selection of treasured prayers from later Anglican tradition has been appended.

As a church leader, you probably have questions about the nature of the updates and changes within this edition. Will the international edition be a good fit for your congregation? Browse this page to get answers to your questions and to download numerous free resources and extra materials to go alongside the book.

Frequently Asked Questions

Want to learn more about this new international edition of The 1662 Book of Common Prayer? Read below for answers to common questions from editors Samuel L. Bray and Drew N. Keane.

What is the 1662 Book of Common Prayer?

The Book of Common Prayer is a volume that provides a framework for prayer, worship, and reading through the Bible, whether at church or at home. It is a much-loved treasure of the expression of Christianity known as Anglicanism. While there are many different books that bear the name, the 1662 revision is the "classic" Book of Common Prayer.

What did you change about the 1662 Book of Common Prayer for the International Edition (IE)?

In the IE there are two types of changes to the 1662.

First, we used prayers for civil leaders and government that are suitable for any nation or constitution. That's a change from the 1662 because it has prayers for the Queen and royal family (though we did keep those prayers, putting them in other parts of the book, so they can be used in British Commonwealth nations).

Second, we updated punctuation and spelling throughout. We revised some particularly obsolete words, or words whose meaning has changed, but we made sure to keep intact the prayer book's distinctive "voice," which is one of its strengths. Here you will find a complete list of changes to the spoken text of the 1662.

Our goal was to make The 1662 Book of Common Prayer (International Edition) as user-friendly as possible for people outside of England without diminishing its doctrinal clarity or compelling language.

What if I'm new to the Book of Common Prayer—what should I read first?

A good place to begin is with Morning or Evening Prayer. One of the additional resources on this page is A Beginner’s Guide to Evening Prayer, and another is A Companion to Morning Prayer. These guides will walk you through the services and answer questions you might have.

Why does the prayer book have old language?

The IE does include modest updates to the language of the 1662 Book of Common Prayer. And a glossary is included at the back of the IE for any words that might be unfamiliar.

Most of the language in the prayer book is old. But it isn't complicated like Shakespeare. Instead, the words of the prayer book have an extraordinary simplicity and gravity. They are as straightforward and timeless as "to have and to hold," "till death us do part." And many have found these words sustaining and nourishing. In The Book of Common Prayer: A Biography, Alan Jacobs notes the impact of the language on Dr. Samuel Johnson:

"The sonorous cadences, the elegant repetitions and antitheses, of [the Book of Common Prayer] may strike some as cold . . . . Johnson, however, did not need his heart warmed, but rather his racing mind calmed. For him, and for many who have felt themselves at the mercy of chaotic forces from within or without, the style of the prayer book has healing powers. It provides equitable balance when we ourselves have none" (pp. 104-105).

Are the readings in the Communion service different from those in other Anglican prayer books?

The readings at Communion in the 1662 Book of Common Prayer (that is, the epistle and the gospel) are ones that were read in the Western Church for centuries both before and after the Reformation. These same readings, with minor variations, are used in other traditional prayer books, such as the 1928 Book of Common Prayer of the Episcopal Church and the 1962 Book of Common Prayer of the Anglican Church of Canada. (View this table showing those minor variations between the Communion readings in the 1662 IE, 1928, and 1962 prayer books.) This ancient annual cycle of Communion readings is not used in the most recent prayer books, which instead use a three-year cycle based on the 1969 Ordo Lectionum Missae of the Roman Catholic Church.

Does the IE use gender-inclusive language for human beings or God?

The IE features only very modest updates to the language of the 1662, so it does not use gender-inclusive language. Our goal was not to propose new language, but to provide a user-friendly edition of the classic text of the 1662 for those around the world today who wish to use it.

A lot has changed since 1662—can the services be adapted to modern use?

The IE provides two appendices that help with adapting the 1662 for modern use.

First, the IE has an appendix of additional prayers that draws from the resources of post-1662 Anglicanism. This appendix provides a greater number of occasional prayers than are in the 1662.

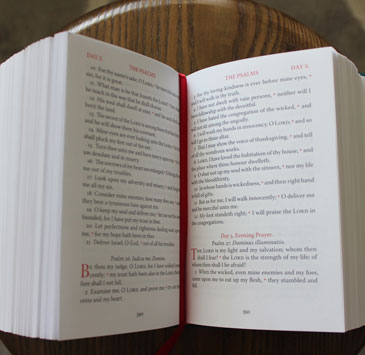

Second, we provide an appendix of additional rubrics. Rubrics (distinguished in this edition by red text) are the instructions for implementing services. As these services have been used day in and day out in the centuries since 1662, customs have emerged that either answer questions the 1662 leaves unanswered or address exigencies unanticipated in the seventeenth century. Many of these customs are reflected in the rubrics of later revisions of the Book of Common Prayer, from which the rubrics in this appendix have been adapted.

Additional resources helpful for implementing these services in church today are provided on this page. There is a liturgical index of hymns, which offers one or two suggestions corresponding to the readings assigned in the 1662 for every Sunday and other holy day. A larger format for the Holy Communion service has been provided, which can be printed for use by the minister presiding at the table. Sheet-music of Anglican chant settings of the Venite and Te Deum is also provided (because the 1662 text of these differs from the text in US hymnals).

Do you include any prayers written after 1662?

We do. The development of Anglican prayer books didn't stop in 1662, and there are some prayers that you might miss if using the 1662. The appendix of additional prayers is drawn mostly from later prayer books from around the world—including editions of the Book of Common Prayer in Canada, England, Ireland, Japan, Kenya, Nigeria, Scotland, South Africa, South India, Uganda, the United States, and the West Indies.

Is there a published source list for the prayers in the Additional Prayers appendix, listing which prayer book or writer was the source of each prayer?

No list has yet been published, but the editors do have information for each prayer about the source or sources it was gathered from. These do not always reflect the first or original source of the prayer, because the same prayer may exist in different versions in different prayer books, and because anonymity has tended to be the rule rather than the exception for prayers included in various editions of the Book of Common Prayer. Source information will likely be included in a future commentary on the IE.

What is the daily office lectionary (Bible reading plan) in the IE?

The IE presents unchanged the daily office lectionary from the 1662 Book of Common Prayer. The core of this Bible reading plan is called "the Table of Lessons." This table provides two readings, the first from the Old Testament (or the Apocrypha) and the second from the New Testament, for each morning and evening. The advantages of this reading plan are its incredible simplicity and ease of use, because it is keyed to the civil calendar (January to December), and each reading is usually just the next chapter in order. If you use this reading plan, you will cover a lot of Scripture—each year you would read nearly all of the Old Testament and you read almost all of the New Testament three times. You would also read large swathes of the Apocrypha.

Some people prefer to follow the church calendar (Advent to Trinitytide) in their reading plan. That's why we've included an appendix with a daily office lectionary that follows the church calendar. It is the Church of England's 1961 daily office lectionary (which was a refinement of the Church of England's 1922 Revised Table of Lessons).

I have the standard Book of Common Prayer published by Cambridge University Press in 2004. I thought it was the 1662 Prayer Book. However the table of lessons does not match the one in your edition. Why are they different? Which one is the authentic 1662 lectionary?

The official The Book of Common Prayer, and Administration of the Sacraments &c., according to the Use of the Church of England, for which Cambridge University Press holds the copyright on behalf of the British Crown, has been legally modified a number of times since 1662. For example, the daily office lectionary was quietly revised (i.e., without any note in the text) in 1871. Then, in 1922, a Revised Table of Lessons following the Church Calendar was added as an additional daily office lectionary. There were also various changes to the rubrics in the twentieth century, including the rubrics of the daily offices and the baptism services. The IE gives you the original 1662 Table of Lessons, and it also includes as an appendix the 1961 Table of Lessons of the Church of England, which was the final revision of the 1922 Table of Lessons.

The “Lessons Proper for Sundays” (page xxix) gives the first lesson for Mattins and Evensong on Sundays. How should I determine the second lesson?

The second lesson is the one given for that day in the calendar, which begins on page xxxiv.

Is the IE authorized for use in public worship?

As a general matter in the Anglican Communion, the "The Book of Common Prayer 1662 is the normative standard for liturgy." That quote is from Principle 55(1) of The Principles of Canon Law Common to the Churches of the Anglican Communion (Anglican Communion Office, 2008). But the answer to this question will differ from church to church. Different Anglican jurisdictions have different means by which texts are authorized for use in public worship.

In the Episcopal Church (USA), a diocesan bishop may authorize a congregation to use the 1662 IE as an alternative to the 1979 Book of Common Prayer under the terms of Resolution A068 of the 2018 General Convention, which authorizes "experimentation and the creation of alternative texts to offer to the wider church" under the supervision of the diocesan bishop. For the Communion service specifically, the 1662 rite may be used in place of the 1979 rite under the terms of 2015 Resolution D050.

In the Anglican Church in North America, diocesan bishops have oversight of the liturgies used within their jurisdictions (Canon 2 of the Constitution and Canons). According to the same canon, the 1662 Book of Common Prayer is one of the prayer books that "shall be permitted for use in this Church," and it is the prayer book identified as the "standard" for Anglican doctrine, discipline, and worship.

Are musical settings of the canticles and other parts of the service available?

For canticles and other commonly sung portions of the services, the text of the IE is almost entirely identical to the text of the 1662. Thus the settings found in traditional Anglican hymnals can be used with minimal modification. For those familiar with the US 1928 prayer book, the largest textual difference from the 1662 is found in the Venite and Te Deum in Morning Prayer. Included in the additional resources on this page are settings of the Venite and Te Deum pointed by Christopher Hoyt, the editor of the Book of Common Praise (2017). Also included in the additional resources is an index of hymns that fit the proper lessons, epistles, and gospels in the 1662 IE.

Are pointed versions of the Psalms available for chanting?

Yes, the Psalms in the 1662 IE have been pointed by Philip Huff, using the pointing system developed by Charles Macpherson, Edward C. Bairstow, and Percy C. Buck for The English Psalter (1925). The pointed Psalter is available here, and the file also includes pointed versions of all the canticles.

Does the Additional Rubrics section contain the 1928 American Prayer Book's Summary of the Law?

No. The form of the summary of the law in the BCP 1928 (US) is unknown outside the United States. We have chosen instead to include in the Additional Rubrics appendix the summary of the law in the Additional Rubrics from the Proposed 1928 Revision of the English Prayer Book and 1929 Scottish Book of Common Prayer; it is quite similar to the form found in the Irish 1926 and Canadian 1962 Prayer Books. This is consistent with the aim of the IE to be a prayer book that can be used around the world, not only in the United States.

Is a service edition available?

Not yet, but one is under contract and is currently being prepared. A large-format version of the Holy Communion service is available as a PDF. If you have questions or need other resources, please reach out to the editors using the form on this page.

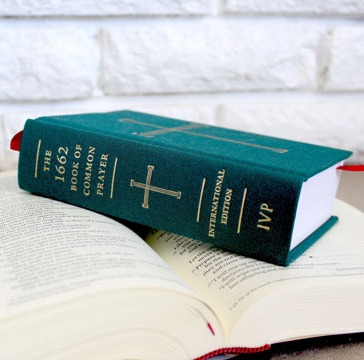

What are the physical dimensions and weight of the book? Does it include a ribbon marker?

The dimensions of the prayer book are 4.3 x 1.7 x 6.3 inches and it weighs 1.2 pounds. Its size is perfect for personal or congregation use. The book includes a single red ribbon marker.

Where the 1662 Book of Common Prayer has "bishops and curates" in the prayer for the clergy and people, why does the 1662 IE have "bishops and pastors"?

The IE uses "pastor" to update "curate" in several places. (It never changes "priest" or "minister.") The reason is that the meaning of "curate" has shifted, at least in English usage outside the United Kingdom. The older meaning was "the one one holding a cure" or "responsible for the cure of the souls in a place." The "cure of souls" meant spiritual charge or oversight of the parishioners, from the Latin "cura." But "curate" has lost these connotations of pastoral care and oversight, and it now typically refers a clergy assistant to a rector or vicar. The English word in current use that most closely fits the idea of clergy with the "cure of souls" in a particular place is "pastor." There is also strong precedent for this usage in the Prayer Book tradition. All of the prayer books before the 1662 (that is, the 1549, 1552, 1559, and 1604 BCPs) use "Bishops, Pastors, and Curates" in the prayer for the church militant, and in the suffrage for clergy in the Litany they have "Bishops, Pastors, and Ministers." And the 1662 Book of Common Prayer has "pastors" in two collects (St. Matthias, St. Peter). The word is therefore already widely used in the Anglican tradition, and it is the closest current equivalent for the older meaning of "curate."

- A Companion to Morning Prayer

- An introductory guide with the prayer book text and commentary

- Family Prayer (Morning and Evening)

- An abbreviated form of Morning Prayer for use with younger children.

- An abbreviated form of Evening Prayer for use with younger children.

- Holy Communion

- Enlarged to letter size for congregants to print

- Table of Textual Changes

- Includes every change to the spoken text of the 1662

- Table of Variations

- Includes changes in the epistles and gospels between this volume and the 1928 and 1962

- Table of Propers in Canonical Order

- Shows how much of the Bible is covered in the proper lessons for Sunday

- The Venite from Morning Prayer

- Pointed (for chanting) by Christopher Hoyt, the editor of the Book of Common Praise (2017)

- The Te Deum from Morning Prayer

- Pointed (for chanting) by Christopher Hoyt, the editor of the Book of Common Praise (2017)

- The Psalms and Canticles

- Pointed (for chanting) by Philip Huff

- J.I. Packer's The Gospel in the Prayer Book

- Collected short writings by J. I. Packer on The Book of Common Prayer (1662)

- Collected short writings by J. I. Packer on The Book of Common Prayer (1662)

- A Companion to Ante-Communion

- An introductory guide to Ante-Communion

- Liturgical Index of Hymns

- Lists hymns for the readings on Sundays and feast days

- The 1662 Daily Office Lectionary

- The calendar and tables of proper lessons for Morning and Evening Prayer

- A Switcher’s Guide to the 1662 Sunday Lectionary

- Notes on the the readings for Sundays

- A Beginner’s Guide to Evening Prayer

- A starting point for using the Book of Common Prayer